True emergency surgical airways performed for genuine cannot intubate cannot ventilate/oxygenate cases are rare in clinical practice regardless of your background speciality. So when they occur and are published as case reports, its useful for those of us interested in learning to be the best at emergency airway management, to carefully review the lessons that can be gleaned from such reports.

In this case report in the Journal of Emergency Medicine, online Jan 2013, the authors from a San Diego hospital emergency department, describe their experience of encountering a difficult airway and initial failed multiple intubation attempts with eventual deterioration to a CICVO situation in a critically hypoxic patient with cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. They describe a unique complication of successful Seldinger technique cricothyrotomy with an uncuffed Melker cricothyrotomy catheter. Their novel approach to managing the complication successfully is useful to know.

Overview of the report :

A 67 yo man with past renal transplant, heart failure and coronary artery disease presents via EMS with acute respiratory distress. Initial exam is suggestive of flash pulmonary oedema with SpO2 readings of 60-90% on mask oxygen. Patient was obtunded . Decision is to intubate quickly and etomidate and suxamethonium is given. A Glidescope VL is used but despite 5 attempts by three physicians including an anaesthesiologist, there is a failure to intubate or even visualise the glottis, due to copious airway secretions and multiple pharyngeal polyps. After the 5 th attempt a CICVO develops and SpO2 falls to 60 % and mask oxygenation is a failure.

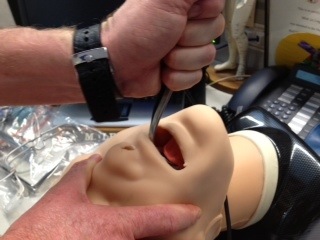

The decision is made to use the only dedicated surgical airway kit in the department, a 4 mm uncuffed Melker Seldinger technique cricothyrotomy kit. This is successfully placed and confirmed in trachea via colorimetric capnometer. SpO2 increases using BVM via the catheter to 90%. Over the next few minutes, resistance to BVM via catheter increases and a noticeable air leak via the mouth develops. This is managed using a double BVM technique with one mask BVM set placed over mouth and nose and synchronised ventilations with the BVM via cricothyrotomy catheter. This leads to SpO2 in high 90’s and a repeat Glidescope laryngoscopy allows a successful visualisation and intubation of the glottis. The Melker catheter is successfully removed after orotracheal intubation is achieved. The patient makes an uneventful recovery and is discharged 6 days later with no neurologic sequelae.

Lessons from the case report :

1.Failure of initial Glidescope videolaryngoscopy – the enemy of any VL or indirect laryngoscopy system are airway secretions and fluids, blood, vomit etc. Be careful if you know these conditions exist in the patient you are about to intubate. This is the second case I have read/heard of in the last 3 months where an indirect laryngoscope system failed due to airway secretions obscuring the field of view

2.Multiple intubation attempts precipitating CICVO – we all know there is reasonable evidence associating multiple intubation attempts with bad outcomes like death so why do we still do it? In human factors research its called task fixation. In high stress high risk situations, the brain can get locked into one train of thought and action. Remarkably there can even be a group reinforcement or so called Lemming effect. One person follows the unsuccessful action of the previous and so does the next. The individual fails each time but collectively as a group they reinforce the need to succeed at that one task. I think video laryngoscopy can make this task fixation worse in some cases. You would think VL may allow task fixation during intubation to be broken earlier i.e everyone watching the VL screen can see if the view is terrible or full of secretions, but I surmise that the intubation group can get fixated on the screen itself and become locked into a group goal of achieving the perfect glottis view on the screen. In this theory, each intubator who fails hands the VL system over to the next group member in the hope that they can get a better view on the screen. Its like a bunch of men trying to fix poor TV reception . Most will keep trying to adjust the screen and channel settings, even the antennae connection. They will do this almost always first, often for multiple attempts before either giving up or climbing on the roof to check the external antennae. This is human nature. We all do this, even women but I have noticed they often look for alternative approach earlier or at least ask for help earlier! This is the second case report I have reviewed whereby multiple VL attempts have eventually led to a CICVO requiring a surgical airway rescue.

3.Consider using a supraglottic airway rescue device earlier – No supraglottic airway device was used after failed orotracheal intubation attempts. Not only might this have avoided the need for a surgical airway but it probably would have solved the airway leak issue encountered subsequent to the surgical airway placement, as long as the SGA was left insitu as well.Several supraglottic airway devices are available now, disposable with gastric drainage channels as well as designed to blind intubate via.

4.Having the right gear to manage the difficult airway – The authors admit that since the case reported, their department has purchased surgical airway kit with cuffed airway catheters and they discuss the use of open cric techniques with bougie and cuffed ETT. They stress the importance of ED physicians knowing a variety of difficult airway techniques and being able to adjust for unexpected complications

Congratulations to the authors for a very useful case report and successful management of a difficult situation!

I encourage you to try to read the complete case report and here is the abstract link

Case report : dealing with a ventilation complication after successful cricothyrotomy

Great post Minh.

I just wonder if they followed the DAS failed RSI guideline, if that would have let to the SGA quicker. This may have bought some time with oxygenation to try to prepare for a surgical airway.

We have a new difficult intubation trolley in Albany, modelled on the Joondalup Hospital one where each drawer corresponds to the next step in the DAS guideline. Excellent for brain freeze moments.

Hi Minh!

Let me go over a part of this case just a little bit to parse out some interesting tidbits:

Following successful cricothyrotomy and ventilation, efficiency of ventilation falls through the Melker catheter over a 5 minute period. The Melker catheter is uncuffed, and the leak is noticed to come from the oropharynx. Combined BVM-Mask and BVM Melker is successful in reestablishing adequate ventilation. Videolaryngoscopy is subsequently successful.

Ok, here we go: Despite adequate medication for RSI, the patient was in complete and total laryngospasm–to the point that experienced endoscopists could not find the larynx. This happens in patients with long term OSA–they develop (functionally) folds of tissue that act like a second epiglottis, and no matter what you do, you can’t find the larynx (I’m speaking from experience here).

Following the successful cric, ventilation began to fall off because the vocal cords finally began to relax and let the ventilation gases out. Then they found the larynx and intubated.

1. The Melker catheter was efficient at providing ventilation, despite the lack of a cuff. An obstruction at the level of the vocal cords, or the base of tongue, allows this catheter to seal and ventilate. The loss of this seal 5 minutes later points to a relaxation of pharyngeal/laryngeal anatomy, thus allowing the ventilation gases to pass out of the larynx/trachea and into the oropharynx.

2. I have seen reasonable doses of succinylcholine fail to relax the vocal cords. I have seen reasonable doses of rocuronium fail to relax the vocal cords. What we all must come to terms with is that sometimes, the drugs do not work as advertised.

3. The use of an SGA could simplify ventilation in the above case, and provide a conduit for repeat oropharyngeal endoscopy (through the mask) during ventilation with the Melker. This gives you another avenue to examine and treat the airway.

4. Those Melkers are short catheters–they are VERY temporary airway solutions. They are used to save lives, and then they need to be transitioned out in a timely manner.

Here’s an analogy: In the “old days”, when houses were built using fuses for electrical safety (instead of circuit breakers like most of us have now), it was possible to replace a burnt-out fuse with a coin to complete the electrical contact–an expedient, but tenuous maneuver. This was intended as a temporary measure if a new fuse was not immediately available, but let’s consider now the next question–how long are you going to leave the coin in the slot intended for an actual fuse? If you leave it in there too long, you risk an electrical fire, and the whole house burns down. I offer that you consider the use of a Melker with the same considerations as the above analogy. The Melker is short, thus it can come out easier–and unless you have done the work of working on a better airway (a tracheostomy below the Melker, for instance), you will not have a plan to maintain the airway beyond that Melker Cric.

5. Should these practitioners have gone to an SGA earlier? Maybe not–I believe that the complete airway obstruction was at the level of the vocal cords in this case–the SGA would have failed to ventilate. Placing the SGA and continuing to attempt to ventilate while the Cric is in progress is an extremely good idea, however. These physicians did the right thing–they kept the patient alive with a surgical airway until the patient’s vocal cords relaxed enough for them to find the larynx with videolaryngoscopy and intubate him.

I’ve crawled out from under the rock of tweeting to see that I missed this great post from earlier. Chatting about airways helps me organize my thoughts on it and helps when it comes to trying to do and teach it! Sorry to rant/ramble but here are some thoughts as I read this:

Point 1: I cannot agree more that different approaches to laryngoscopy have different pros & cons and that high fluid situations put indirect or image based laryngoscopy (IL) [includes VL, AirTraq etc] at a distinct disadvantage: the optics are in the airway where the fluids are with IL(VL)! This is opposed to direct laryngoscopy where the optics are outside and so will not get blinded by fluid.

In both cases, multiple suctioning is required with consideration to control the source of fluid (e.g. direct pressure to stop airway bleeding, foley the epistaxis, NG decompress the belly full of blood). One advantage of IL(VL) is that it allows multiplayer airway management (HT @emupdates and @emcrit I believe: there can be two “suctionists” in addition to the intubator looking at the airway and managing fluids soiling the airway while simultaneously trying to secure the airway). This goes back to what is the best approach, knowing what difficulties will pose to it and addressing those difficulties in plan A. If that fails then plan B must be different to try to solve the problem!! As must plan C and plan D!!

Point 2: If the first attempt failed, doing the same thing will likely also fail. Multiple attempts lead to airway trauma, leading to a more difficult airway to manage whether intubating or rescue ventilating/oxygenating: more swelling, bleeding and disruption. I feel it is important to assess after each failed attempt as to why the failure occurred, and address the difficulty encountered. It is crucial to know how to deal with difficulty when encountered; subsequent attempts must always change something. Changing operator may not be change enough if one does not know the difficulty and get around it.

Point 3: Minh, I absolutely agree about the SGA. I think of BMV as your first backup parachute and SGA should be one’s automatic secondary backup chute (and of course with initial denitrogenation if time and ongoing apneic oxygenation). I like to think of these as the rapid “have no time” rescue airway/oxygenation tools. Whenever the sats are down [and the Roller Coaster oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve (HT @robjbryant13) as well as the pulse ox lag (HT @emcrit) suggests that this should be triggered at around 93%], one should rapidly move to reoxygenation first with BMV and if that does not work, move to rescue SGA and consider prepping for the final backup of cric. If SGA does not work immediately and one has already multiple attempted intubation or the airway is too difficult (surgically inevitable?), one should move to the rapid surgical airway that is readily available: as you know my favourite is scalpel bougie open cric which is rapid, reliable, can work in high BMI, gets a secured airway and only needs the scalpel, bougie, 6.0 ETT and your finger!

@ Jimmy D: wow, thanks for that perspective on what could have happened to the airway.

Thanks again for the chance to think (and obsess) more about airways!

Yen

Amen to your comments and contributions (Yen). We have lots to discuss. The key is to be relentless, “simple”, and not ignore what situation is presenting you with. To accept fully what life brings to your door is synonymous with Enlightenment in at least one spiritual tradition. And We all seek airway Enlightenment.